The Parthenon Mosque: An Alternative View

Maziar Mohajer

Keywords: Parthenon, Kufic inscriptions, alternative history, 1687 Venetian bombardment, epigraphy, revisionist historiography, New Chronology.

Introduction

This document presents an alternative perspective on the history of the Parthenon. Traditionally, the Parthenon is understood to have evolved from an ancient Greek temple into a Christian church before its conversion into an Ottoman Mosque.

Central to this alternative interpretation is the examination of fragmentary Kufic Arabic inscriptions discovered around the Acropolis. These inscriptions contain a Quranic verse (Surah IX, 18) along with additional historical references, which collectively suggest the existence of an Islamic—or proto-Islamic—religious site in Athens, dated to the late 10th or early 11th centuries, according to scholars.

The first hypothesis is that the Kufic script was part of the foundation inscription of the Parthenon Mosque. The analysis also suggests that the scattered fragments, likely caused by the explosion of 1687, point to their original placement in the minaret of the Parthenon.

By aligning these findings with broader historical frameworks such as the proto-Islam school of revisionism and aspects of the New Chronology, this observation forms the basis of the "proto-mosque theory, which argues that, between the 10th and 14th centuries, the Parthenon incorporating both Christian and Islamic elements was built on the Acropolis.

Conventional History of the Parthenon

The Parthenon, standing atop Athens' Acropolis Hill, has undergone multiple transformations—from an ancient temple of Athena to a church, an Ottoman Mosque, and finally a globally recognized symbol of classical antiquity.

Originally built in the mid-5th century BC as a temple dedicated to Athena Parthenos, it housed her colossal gold-and-ivory statue and also functioned as a treasury (Neils, 2005). In Late Antiquity, sometime in the last decade of the sixth century AD, after suffering fire damage, it was converted into a Christian church known as "Our Lady of Athens," serving first the Byzantine community and later functioning as a Latin cathedral (Ousterhout, 2018). This conversion involved adapting the apse, removing altars, and whitewashing walls (Palagia, 2013).

Following the Ottoman conquest of Athens in 1458, the Parthenon was transformed into an Islamic Mosque (Etlin, 2008). The conversion to a congregational mosque likely occurred between 1466 and 1470 (Kallet, 2010). The first mosque was an adaptation of the existing church structure, with the apse becoming a mihrab (prayer niche), the tower—originally a Christian bell tower—extended to serve as a minaret, and a minbar installed (Neils, 2005). This structure, known as the "fortress mosque" (Hurwit, 2012), was devastated during the Venetian bombardment of the Acropolis in 1687.

Below is a timeline summarizing key phases in the Parthenon’s history:

| Period | Event |

| 490–488 BC | Construction of the Older Parthenon begins after Athens' victory at the Battle of Marathon. It replaces an earlier temple, the Hekatompedon. |

| 480 BC | The Persians sack Athens, destroying the Older Parthenon and other Acropolis structures. |

| 447–432 BC | Pericles commissions the Classical Parthenon. Architects Iktinos and Callicrates design it, and Pheidias oversees the sculptural program. |

| 438–431 BC | Architectural elements and decorations are completed. The colossal statue of Athena Parthenos is placed inside. |

| Late Antiquity | A fire damages the Parthenon. It is later converted into a Byzantine Christian church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. |

| 12th century AD | Modifications are made to the church, including a larger apse replacing the earlier one. Pagan figures on metopes are defaced. |

| 1458–1470 AD | After the Ottoman conquest, the Parthenon becomes a mosque. Minor modifications include converting the apse into a mihrab and adding a minaret. |

| 1687 AD | The Venetian bombardment causes massive destruction when Ottoman forces store gunpowder inside the Parthenon. |

| 1708 AD | A second, smaller mosque is built within the ruined Parthenon. It remains in use until Greece's independence. |

| 1830s–1843 AD | After Greece gains independence, Ottoman structures are removed to restore the ancient site for archaeological study. |

Afterward, a second, smaller, free-standing mosque was built inside the ruined shell, in the former naos, likely in the early 18th century (Haselberger, 2014). This domed structure, described as "shabby" (Szegedy-Maszak, 2013), was visible in the first photograph of the Parthenon taken in 1839 (Barletta, 2018). This second mosque was dismantled in 1843 by the newly liberated Greeks to allow for archaeological work (Ousterhout, 2018).

Discovery and Description of the Kufic Inscriptions in Athens

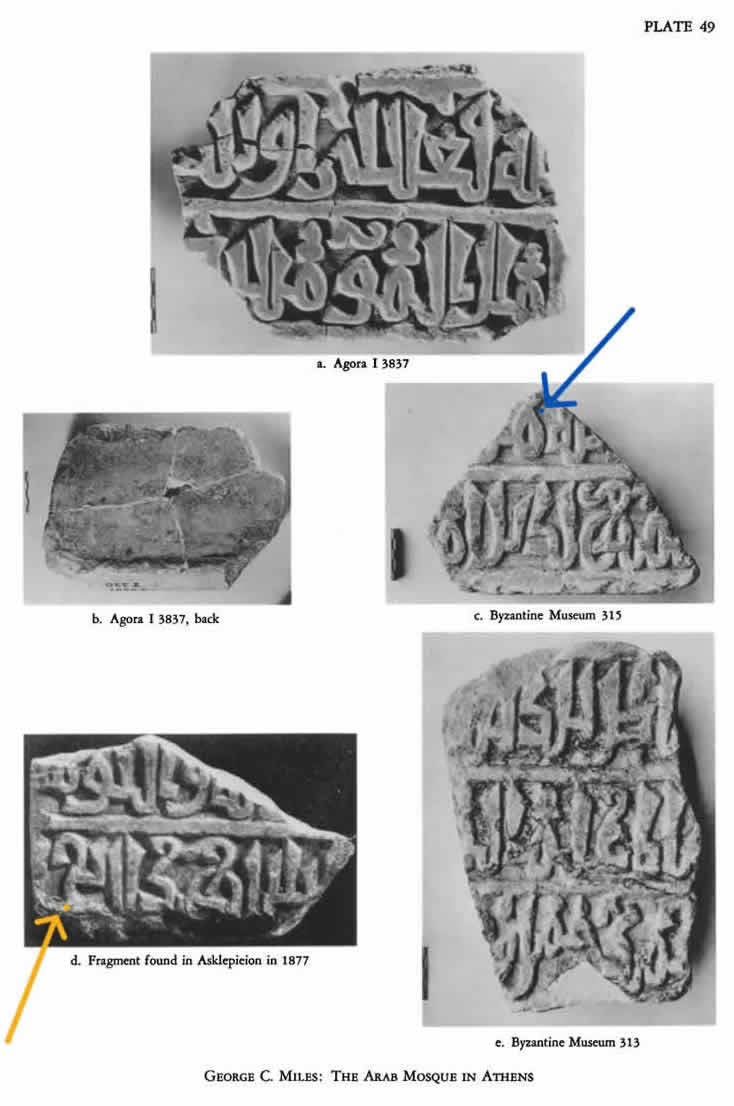

This paper is based primarily on the work of George Miles, an American numismatist, who examines the discovery and interpretation of Kufic inscriptions in Athens in his article” The Arab Mosque in Athens”. Miles reconstructs these fragmentary inscriptions, shedding light on their historical significance and potential connection to an early Islamic presence in the city.( Figure 1 and Table 2)

The article is fascinating. Scattered fragments are placed together to uncover both Quranic verse and historical text. It did not dismiss findings that challenge conventional perspectives. The article critically reexamines earlier interpretations. As a scientific work, I encourage readers to engage with the full text, but here is a summary of its key points.

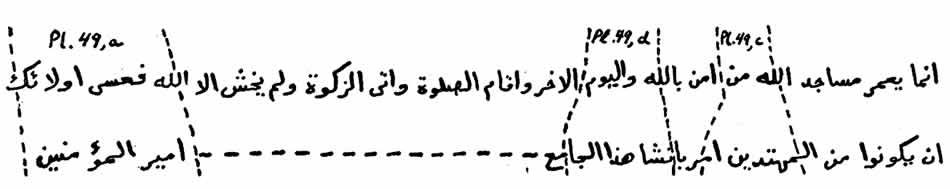

Miles reconstructs Kufic inscriptions from Hymettian marble fragments found in Athens, revealing a Quranic verse (IX, 18) alongside historical text (Figure 3). The fragments of the Kufic Arabic inscription were found in several locations (Table 2 and Figure 2). The inscription found on several fragments in Athens provides significant evidence of a mosque foundation text. The following table summarizes the main details of the discovered fragments:

| Fragment ID | Description | Location Found | Current Location | Discovery Date | Content | Context |

| Agora I 3837 (P1. 49, a) | Four joining fragments | Modern house wall north of the Church of the Holy Apostles, ancient Agora, Athens | Not specified | March 19, 1936 | Upper line: " [Al]lah. For perhaps these-" (From Qur'an IX, 18) Lower line: " amir al-mu'minin" ("Commander of the Believers") | Qur'anic verse followed by a historical inscription; possible traces of an earlier first line |

| Lost Fragment (P1. 49, d) | Known only through a photograph | Asklepieion excavations | Possibly among scattered stone fragments on the Acropolis | 1877 | Upper line: " .... [Alla]h and the Day...... " (From Qur'an IX, 18) Lower line: " .... [f]ounded this mos[que ?]. .-.. " | Confirms connection with Agora I 3837; historical inscription references mosque construction |

| Byzantine Museum no. 315 (P1. 49, c) | Smaller fragment | Asklepieion area | Byzantine Museum, Athens | Not specified | Upper line: Two complete letters identified as lam-ha (Allah) and mim-nun (man) Lower line: " al-muhtaddn" ("those who are rightly directed") followed by "amara" ("ordered") | Identified as belonging to the same inscription as Agora I 3837 and Lost Fragment |

| Byzantine Museum no. 313 (P1. 49, e) | Fragment found in excavations | Roman Agora, within the Tower of the Winds | Byzantine Museum, Athens | Not specified | First line: Possible reading includes "li'ladhina" Second line: Possible word "sharr" Third line: The first three letters appear to read h-m-d, possibly part of "Muhammad" or "Ahmad"; following text "acmala" or "acmal" ("made by" or "work of") | Kufic script suggests the fragment belongs to the same column drum as the others; two lines remain undeciphered |

Table 2: Details of fragments, including locations, descriptions, inscriptions, and reconstructions.

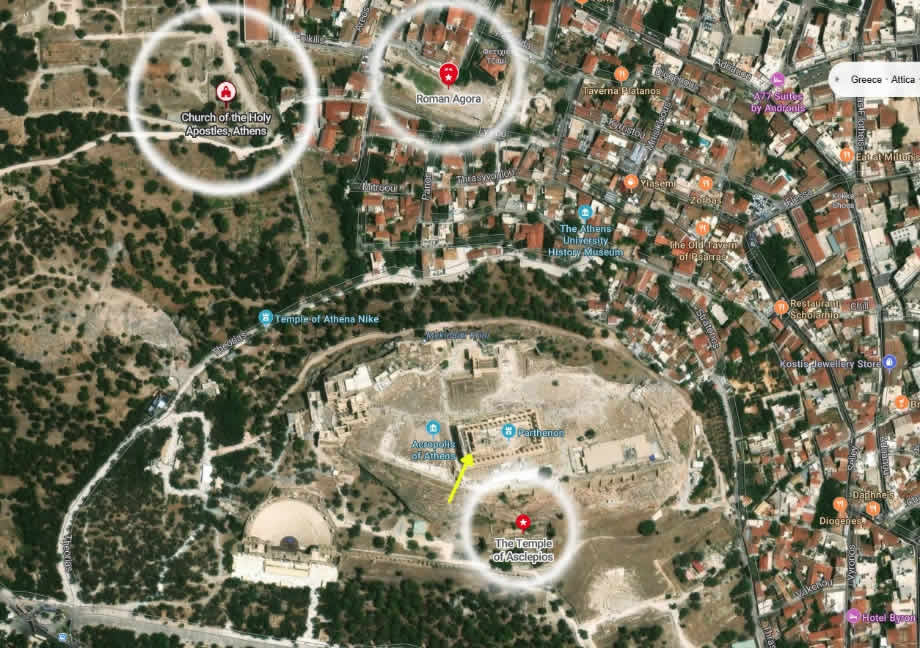

Figure 2: The fragments of Kufic inscriptions were discovered in several locations across Athens, including the Ancient Agora, specifically near the Church of the Holy Apostles; the Asklepieion area, situated on the southern slope of the Acropolis; and the Roman Agora, within the Tower of the Winds. These scattered finds suggest they were originally part of a larger inscription, possibly from the Parthenon Mosque’s minaret—shown by a yellow arrow—and were dispersed due to the 1687 Venetian bombardment. Some scholars believe the Grand Mosque was located in the Asklepieion area, while others note that no traces of a mosque have been found there. Two fragments were discovered in Asklepieion, while other fragments were found north of the hill. Some suggest that local people may have carried them to more remote areas. However, the initial location must have been on the slope of the hill. In my view, only a strong explosion could scatter small marble fragments across such a large area.

The Quranic Passage

This passage is partially preserved across multiple fragments, including Agora I 3837, the lost fragment from the Asklepieion, and Byzantine Museum no. 315 (Table 3)

The upper line of the inscription contains a fragment of Surah IX, verse 18, which states: "Verily only he shall visit the mosques of Allah who believes in Allah and the Day of Judgment and who is constant in prayer and pays the legal alms and fears only Allah. For perhaps these may be among those who are rightly directed."

it should be remarked that the passage, Qur'an IX, 18, is one that is entirely suitable for the adornment of a mosque. In fact, its use for this purpose is common and widespread. The earliest recorded epigraphical occurrence of the verse appears to be on a number of mosques (table 3). Thus, there is good precedent for the epigraphical use of this particular passage from the Qur'an from at least early ‘Abbasid times onward. Incidentally the context of the passage is equally apposite for the embellishment of a mosque, and is relevant to a mosque in a foreign or distant land beyond the Dar al-Islam.

| Mosque | Location | Date |

| Mosque of the Prophet | Medina | 162–165 H. (778–782 CE) |

| Mosque of Ibn Tulun | Cairo, Egypt | 265 H. (878/9 CE) |

| Displaced Mosque Inscription | Cairo, Egypt | 402 H. (1011/12 CE) |

| Inscription from Nablus | Nablus, Palestine | ca. 411 H. (1020 CE) |

| Great Mosque of Esneh | Esneh, Egypt | 474 H. (1081/2 CE) |

| Minaret of the Great Mosque | Aleppo, Syria | 483 H. (1090/91 CE) |

This verse emphasizes the significance of faith, devotion, and responsibility in maintaining places of worship. It has been frequently inscribed in historical mosque inscriptions.

The Historical Text

the "Historical Text" refers to the portions of the Kufic inscription fragments that extend beyond Surah 9, Verse 18, offering additional details on the mosque’s foundation and patronage. The historical text is primarily found on the lower line of some of the reconstructed inscription fragments. I provide the key point of Miles' interpretation:

The lower line of the inscription contains the phrase "Commander of the Believers. This title was exclusively used by Caliphs in this period, suggesting a connection to Islamic authority. Additionally, the lost fragment includes the phrase [f]ounded this mos[que ?], indicating that the inscription recorded the construction or adaptation of a mosque. The reconstructed text from Byzantine Museum no. 315 suggests the phrase ordered preceding "the building of", reinforcing the foundation inscription hypothesis. The mosque’s construction was likely ordered by a patron associated with the ruling Caliph.

The dating of the inscription is estimated to fall within the second half of the 10th century to the first half of the 11th century CE, based on epigraphic comparisons and historical context. The presence of the Caliph’s title implies that the builder or patron had a direct connection to the ruling Caliph—either as a client, official, or honorary title-holder. While the precise historical circumstances remain debated, the inscription provides strong evidence of an Islamic religious structure in Athens during this period.

The article evaluates the third word in this phrase, debating whether it should be "al-Jami'" (الجَامِع)—which denotes a congregational mosque—or "masjid" (مَسْجِد), meaning mosque in a general sense. While earlier epigraphic traditions favored masjid, the reading Jami' is not ruled out

Since each word holds significant weight in our discussion, here is how the author explains their meanings.

“Amir al-muminin" امیر المومنین: means Commander of the Believers: in this general period and area of the Islamic world was assumed only by the Caliph." In view of the silence of the historians with regard to any occupation of Attica by the Arabs or their co-religionists, one can with fair confidence exclude the possibility that the title here refers directly to the Caliph. The source presents two other possible explanations for the appearance of this title on the Athenian inscription:

- The building was erected "in the time of," or "in the days of," a specific Caliph.

- The builder or patron of the mosque held a title or honorific compounded with Amir al-muminin as the second element.

“amara" (أَمَرَ): means "ordered". The inscription states that someone ordered the construction of the mosque.

"Cami/ Jami'" (جَامِع): The article discusses the third word in this phrase, noting that while the reading "al-Jami'" (الجَامِع), meaning "mosque" or specifically "congregational mosque. The word "Jami'" is used for the Friday or congregational mosque. "masjid" possibly being expected based on earlier epigraphical usage. Regardless of the precise term, the presence of the Qur'anic verse affirming mosque legitimacy strongly supports the interpretation that the inscription refers to the establishment of an Islamic place of worship in Athens.

As I will elaborate further, Miles faces certain challenges in his interpretation of the historical text. It would be more appropriate to refer to the mosque as the Grand Mosque in our discussion, from this point forward.

Below is a table that compares the terms "masjid" and "jamiʿ"

| Aspect | Masjid | Jamiʿ |

| Definition | A general term for any place where Muslims perform daily prayers. | A specific mosque designated for hosting the main congregational (usually Friday) prayer; it serves as a central assembly place for the community. |

| Etymology | Comes from the Arabic root s-j-d (س-ج-د), which means “to prostrate,” emphasizing the act of prayer. | Derived from the Arabic root j-m-ʿ (ج-م-ع), meaning “to gather” or “to assemble,” reflecting its function as a gathering point for communal worship and broader social activities. |

| Traditional Usage in Islamic Context | Used broadly for mosques of any size—from local prayer houses to larger community mosques. | Traditionally reserved for the principal or “grand” mosque of a town or city, where the Friday (jumuʿah) prayer is held and where important religious, social, and sometimes political functions occur. |

| Cultural and Historical Significance | Often denotes a neighborhood or local place of worship without implication of central authority. | Carries additional prestige due to its role as the community’s central mosque. Historically, it has been associated with leadership and governance—as the caliph or local ruler might lead the Friday prayer—underscoring its elevated status. |

| Epigraphical Context | Some earlier epigraphical traditions and inscriptions expected the use of “masjid” to designate a generic mosque. | The article’s critical point hinges on the reading of the lost inscription fragment: the initial letter clearly corresponds to “jamiʿ” (beginning with ج) rather than “masjid” (which would begin with م). This supports the interpretation that the building was intended as a grand congregational mosque rather than a modest local one. |

| Modern Usage | Today, both terms are often used interchangeably; however, in formal or scholarly contexts “jamiʿ” still implies prominence and scale while “masjid” remains the generic term. | Even in modern usage, when one refers to a “jamiʿ” mosque (or “Jamiʿ Mosque”), it underscores a building with historical, social, or political relevance beyond routine daily prayers. |

Figure 3 illustrates Miles' interpretation of the Kufic script, highlighting elements of the inscription.

When the Grand Mosque was built?

Miles notes that while dating Kufic styles presents challenges due to variations, the specific characteristics of this inscription, when considered alongside historical context, indicate an approximate timeframe for the mosque’s construction. Based on epigraphical evidence from marble fragments the Arab Mosque in Athens is estimated to have been built between 961 and 1058 AD (350–450 H.). This dating is primarily derived from paleographical analysis of the Kufic script, particularly the presence of bow-shaped ligatures descending below the baseline, which suggests a period no earlier than the late 10th century and no later than the late 11th century.

Other scholars, based on fragment readings—including the phrase "[f]ounded this mos[que ?]"—also affirm the likely presence of a mosque around the year 1000 AD.

Where was the Grand Mosque?

The discovery of inscription fragments in different locations led to varying interpretations regarding the presence of a mosque in the Asklepieion area. Some scholars proposed that a mosque once stood at the site. However, later investigations found no architectural remains confirming the existence of a mosque within the Asklepieion itself. Travlos found no trace of a mosque among the actual remains (Figure 6).

Despite the absence of structural remains, epigraphical evidence—including the Quranic verse and historical references—supports the existence of a mosque in Athens.

Who built the Grand Mosque?

Setton argues that a small Muslim colony likely existed in the city around the year 1000. This community had a mosque on the site of the ancient Asclepieum. Muslim craftsmen were present in Athens, contributing to various architectural projects. He cautions against speculative historical interpretations when factual evidence is insufficient, emphasizing how imagination often distorts historical accuracy. He critiques Kampouroglous' claim of a forcible and destructive Arab occupation of Athens in the tenth century, arguing that the available historical and archaeological data are too tenuous to support such a conclusion (Setton, 1954).

Overall Scholarly Conclusion

In summary, the presence of Kufic inscriptions on Hymettian marble fragments in Athens- scattered around the Acropolis- suggests the existence of a mosque in the city between the late 10th and early 11th centuries. The date is based on stylistic features of the Kufic script. However, its origins—whether founded by Muslim settlers, captives, or artisans—remain debated. The mosque’s precise location is also uncertain, with some scholars attributing it to the Asklepieion, though no structural remains confirm this hypothesis. While some theories suggest a Saracen occupation of Athens, the historical evidence is inconclusive, indicating a small Muslim community rather than military control. This is how the article concludes.

Kufic Script: Origins, Characteristics, and Historical Timeline

Since readers may be unfamiliar with Islamic calligraphy, here's a brief overview (Table3): Islamic calligraphy features a variety of styles that evolved in a roughly chronological order, each reflecting its era's artistic and cultural influences. For example, the early Kufic script—with its angular, geometric forms—eventually gave way to more fluid styles, eventually disappearing as these newer scripts took precedence.

Kufic script originated in the early Islamic period (7th century CE) as the earliest angular and geometric form of Arabic calligraphy. It features geometric shapes with straight lines and angles, often without vowel marks or diacritical dots in its earliest forms. Kufic flourished from the 7th to the 10th century, reaching its artistic peak by the late 8th century It remained dominant until about the 11th century, after which it gradually declined by the 13th century due to the rise of more cursive scripts like Naskh and Thuluth, which were easier to write and read (Wikipedia, 2025; Britannica, 1998; Timetoast, 2025).

| Period |

Development of Kufic Script |

| Origins | Derived from a modified Nabatean script, believed to have originated before Kufa’s founding (early 7th century CE or earlier). |

| 7th Century CE | Developed and widely used for copying the Qur'an by order of Caliph Uthman ibn Affan; primary script for Qur'anic manuscripts. |

| 8th-9th Century CE | Reached its fullest development ("perfection") by the late 8th to early 9th century CE (ending around 814 CE). Evidence suggests it existed earlier. |

| Until 11th Century CE | Remained the dominant script for Qur'anic manuscripts until the 11th century, before being replaced by more cursive scripts like Naskh and Thuluth. |

| Decline | By the late 13th century, Kufic became largely obsolete due to its complexity and the rise of other scripts like Thuluth, Diwani, and Ruq'ah. |

Controversies in scholarly views on the Kufic script fragments (mosque foundation):

- The mosque is identified as a large Grand Mosque (Jami) in Athens, not a smaller mosque (Masjid), as some scholars propose.

- The dating of the large mosque suggests it predates the Ottoman era (10th to 11th century), a period when no Arab or Muslim presence in Athens is recorded.

- The title "Commander of the Believers" typically indicates a connection to Islamic authority, yet there are no recorded Muslim conquests in that era.

- The entire Grand Mosque has disappeared, with no known location or historical record of its whereabouts.

- A small community of Muslim captives could not have built a Grand Mosque (Jami) under the command of a Caliph, given their limited resources and overall status. In fact, identifying the mosque as a Jami contradicts the idea of a small community, since a Jami typically serves a large Muslim population.

- There is no definitive explanation for why fragments from a small marble slab are dispersed around the Acropolis hill.

- There is no explanation why a fragment was lost. Equally, no rationale is offered for the possibility that it might still be somewhere among the stone fragments scattered across the Acropolis.

- Why did Miles hope that other fragments somewhere around the Acropolis would provide the true answers?

- According to Professor Miles, during the period and in the region relevant to this inscription, the title the Commander of the Believers, was exclusively used by the Caliph. He indicates that this title was held by the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad, the Fatimid Caliph in Cairo, and the Umayyad Caliph in Cordoba. On the other hand, this title cannot be related to an Ottoman Mosque. According to academic sources, Ottoman rulers did not use the title Amir al-Mu’min in as their chief title. Early Islamic dynasties such as the Umayyads and Abbasids employed that title but by the time of the Ottomans, the rulers had largely shifted to other titles. Scholars like Gibb (1979) and Finkel (2005) emphasize that its usage was limited and not central to the Ottoman imperial titulature.

While the foundation inscription is securely dated to the 10th or 11th centuries, there is no historical record confirming the presence of a Muslim community in Athens, nor has any archaeological trace of a mosque been documented. This absence of evidence is particularly striking considering that a mosque of substantial size—capable of accommodating large congregations for Friday prayers and constructed under the command of a "Commander of the Believers"—would likely have generated both significant historical records and enduring physical remains.

Hypothesis 1: Identifying the Enigmatic Mosque with the Parthenon Mosque

Here is my hypothesis 1: I suggest that substantial evidence indicates that the fragments belong to the Parthenon Mosque, previously known as Cami'-i Kal'e-i Atina (جامع قلعه آتینا) the Grand Mosque- Fortress of Athens. The fragments were scattered by the 1687 explosion, likely from its minaret. The inscription confirms its status as a Jami (the Grand Mosque), and in addition, historical accounts verify congregational worship inside the Parthenon.

Identification of the Grand Mosque

The inscription explicitly refers to the construction of a Grand Mosque. Notably, scholars have exhibited reluctance in acknowledging the term Jami' (جامع), despite its clear presence in the Kufic script. While deciphering Kufic inscriptions presents inherent challenges, the distinction between ج (J) for Jami and م (M) for Masjid in Arabic is unmistakable. The lost fragment contains a word beginning with ج (J) rather than م (M).

Contextual Considerations

Documentation on Ottoman mosques in Athens remains scarce. However, historical urban patterns indicate that each city typically housed one Grand Mosque, with additional small mosques distributed across neighborhoods. Given that all inscription fragments have been discovered in the vicinity of the Acropolis, it is reasonable to conclude that they belonged to a nearby Grand mosque, most likely Cami'-i Kal'e-i Atina over the Acropolis hill.

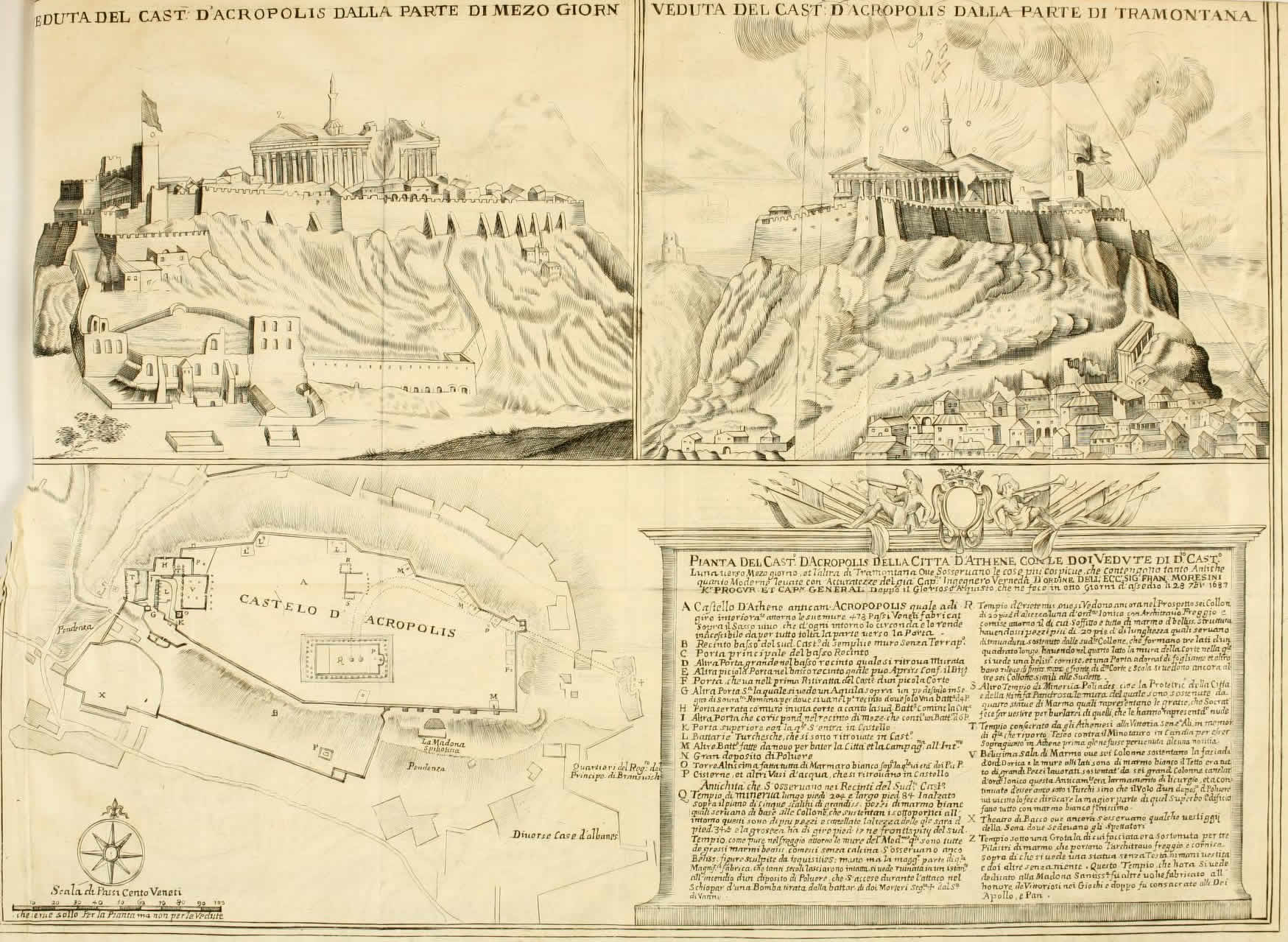

The Parthenon Mosque and the Explosion

Based on the historical records, Parthenon Mosque was destroyed during the Siege of the Acropolis in 1687. “The Ottomans had repurposed the building as a gunpowder magazine, but on September 26, 1687, a Venetian mortar shell, struck the Parthenon. The impact ignited the stored gunpowder, causing a catastrophic explosion that severely damaged the central portion of the Parthenon, destroying its roof and walls, and effectively annihilating the mosque functioning within it.”

The explosion provides a clear explanation for the distribution of fragments around the slopes of the Acropolis. These fragments have been discovered primarily on the southern slope, as well as in the northwest and northern areas of the hill.

Additionally, Miles speculated that fragments might still be scattered around the Acropolis, awaiting discovery. The force of the explosion dispersed a relatively small marble slab across the Acropolis hill. (Figure 4)

The Minaret and the Explosion

Historical sources state that the Venetian bombardment in 1687 toppled the minaret. Other source notes that the old minaret is shown standing in views during and immediately after the explosion but not in the 18th-century views, suggesting it may have fallen shortly after explosion. This suggests that although damaged or destabilized by the explosion, it may have remained partially standing for some time (Figure 5)

It is plausible that the foundation inscription was originally placed on the minaret. Given the locations where the fragments were discovered, it is reasonable to assume that the inscription was positioned atop a structure of considerable height. The explosion would have propelled the fragments in various directions, dispersing them across relatively distant areas.

Notably, two fragments were found in the Asklepieion area, while the minaret itself was situated at the southwest corner of the Parthenon structure. A review of maps and photographs of the Acropolis reveals that the Asklepieion area lies directly below the site where the destroyed minaret once stood. Some archaeologists have hypothesized the existence of a mosque at or near the ancient Asklepieion of Athens, located on the southern slope of the Acropolis. However, no physical traces of such a mosque have been identified among the actual remains at the Asklepieion site. In fact, archaeologists have discovered only some fragments of the foundation inscription alongside the possible debris of the minaret. The Grand Mosque has been in a short distance just at the top of the hill.

Comparatively, the minaret of the Great Mosque of Aleppo also featured a foundation inscription.

Historical texts document instances of prayer within the Jami', including an account by the Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi, who visited the Parthenon Mosque in 1667. It was a Grand Mosque at the time. He describes the faces, kneeling, and prostrations of worshippers being reflected in the surrounding walls, as though in a mirror (Fowden, 2019).

Scholarly Oversight

Why could the scholars not locate the enigmatic mosque? And why did they overlook the possibility that “Jami” referred to the Cami'-i Kal'e-i Atina? The explanation lies primarily in their reliance on historical records and accepted chronology. Scholars compared the inscription’s style with other dated examples to estimate when it was made. Their analysis places the mosque’s construction in the late 10th or early 11th century, contrasting with historical records that claim the Parthenon was converted into a mosque in the 15th century. The Parthenon served as a Christian church under both Byzantine Orthodox and Roman Catholic traditions from approximately the late 5th or 6th century AD until the mid-to-late 15th century AD. According to conventional historiographical perspectives, the structure functioned as a church during the 10th and 11th centuries, having originally been established centuries earlier as a Greek temple.

However, the foundation text clearly indicates that the building was established as a mosque from the very beginning. This is significant because, according to historical records, the Parthenon was never founded as a Jami (a congregational mosque). Instead, the Parthenon’s history is marked by a series of transformations—from its original purpose as a pagan temple to a conversion into a Christian church, and later, its use as an Islamic Mosque.

Let's review two considerations. First, there is a foundation inscription from a Grand Mosque near the Acropolis in Athens that historians and archaeologists have not adequately explained based on conventional historical accounts. Second, it is plausible to argue that the marble bearing the inscription originally belonged to the minaret of the Grand Mosque of Athens (often referred to as the Parthenon Mosque), which was scattered around the Acropolis hill as a result of a powerful explosion. These observations suggest that further inquiry into the historical evidence related the Parthenon is justified.

Figure 4: The Parthenon Mosque, known as Cami'-i Kal'e-i Atina, was destroyed during the Siege of the Acropolis in 1687. A powerful explosion propelled fragments in various directions, dispersing them across relatively distant areas. The minaret, visible among the falling debris on the hill, was likely affected by the force of the blast, contributing to the widespread distribution of inscription fragments.

Figure 5: The same scene is depicted in numerous illustrations, and even a medal was created in its honor. Why was it commemorated in such a way?

Figure 6: The current state of the Acropolis shows that the Asklepieion area lies directly below the Parthenon, particularly where the toppled minaret once stood. A mosque, especially one of substantial size, could not have existed in such a small and sloped area. The mosque has not disappeared—though partially destroyed, its remains are still visible. All so-called Frankish and Ottoman structures, notably the citadel, have been removed.

Hypothesis 2: the "Proto-Mosque Theory"

This is the second hypothesis: The Parthenon was built as a mosque and not a pagan temple and not even a Christian church. I admit that it is too radical historical revision. It ignores two important historical periods lasting for about two thousand years.

Let’s explore alternative views on history and religion to see if we can find arguments supporting the hypothesis.

Alternative Religious Frameworks: School of Islamic Revisionism

The proto-Islam school of Islamic revisionism challenges traditional accounts by suggesting that early Islam emerged gradually from a fluid religious milieu rather than from a sudden, definitive breakthrough. Proponents contend that early Islamic identity was marked by an evolving interplay of diverse monotheistic traditions, with nascent communities expressing their beliefs in a context of continuous negotiation and adaptation. (Crone & Cook, 1977; Wansbrough, 1977; Hoyland, 2015).

Fred Donner and other scholars argue that the Quran reflects the early Believers’ Movement, which may have included non-Muslims and is often described as proto-Islamic rather than distinctly Islamic in its earliest phase. Characterized by ecumenical monotheism, this movement did not see itself as forming a separate religious confession but as continuing the message of earlier apostles, allowing pious Jews and Christians to participate without renouncing their original religious identities. Some early Believers were indeed Christians or Jews, and Donner suggests that the transition from this inclusive "Believers' Movement" to "Islam" as a distinct religion separate from Christianity and Judaism occurred gradually, particularly under the Umayyad caliph 'Abd al-Malik.

Alternative Historical Frameworks: New Chronology

Interestingly, New Chronology too believes that Islam emerged gradually from early proto-Christian sect and evolved over centuries. Also, proponents argue that the Parthenon was originally established as a medieval Christian temple with elements of other religions.

Morozov and Postnikov, argue that Islam did not emerge in the 7th-century Arabian Peninsula with a historically verifiable Prophet Muhammad and a Quran compiled shortly after his death. Instead, it is suggested that Islam developed over centuries from early proto-Christian Hagarene sects, possibly linked old Believers fleeing Byzantine religious reforms. The early perception of Hagarism as a Christian sect underwent a significant shift in the 11th–12th centuries, with the Byzantine Church’s anathematization of Mohammed in 1180 serving as a decisive turning point. At this point, the Hagarenes had elevated their prophet Muhammad above Christ, formally separating from Christianity. The final division of the previously unified proto-Christian doctrine into four distinct religions—Catholicism, Orthodoxy, Islam, and Judaism—occurred in the 11th century, with former Hagarene sects that embraced the veneration of Muhammad evolving into Islam (Postnikov, 1997).

According to Postnikov, the exact date of the Parthenon's original construction and its early conversion into a church remains uncertain, with available documentation potentially unreliable. However, its status as a "fully preserved, functioning church" that was heavily taxed for its completion in the 13th century supports the argument that significant construction or finishing work occurred during the Frankish period.

Based on New Chronology, the Parthenon was a medieval Christian temple, likely built in the 13th or, more specifically, the second half of the 14th century A.D. This perspective suggests that the transformation of the Parthenon into a mosque in 1460 may not have been a radical shift but rather part of a broader historical process in which religious elements coexisted before being formally categorized as belonging to distinct traditions. The presence of structures like a high belfry, which could have later been identified as a minaret, supports the idea that Christian and Islamic architectural features may have been intertwined before their separation. This interpretation challenges the conventional view that the Parthenon was exclusively an ancient Greek temple before its later conversions, instead proposing a more fluid religious identity through time. (Fomenko, 2003-2015, p. 903)

Fomenko largely omits discussion of the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates. He briefly suggests that the Umayyad Caliphate was not an independent empire from the 7th century AD but rather a reflection of the 15th–16th century union between Russia-Horde and the Ottoman Empire. According to his theory, Islam and the Quran originated in the 15th century with Muhammad the Conqueror. However, he has recently acknowledged Arabic as the Empire’s ancient language, possibly emerging when the Empire was founded in the Nile Valley (Fomenko & Nosovsky, 2023). He dates the Empire’s origins to the 10th–11th centuries AD, emphasizing Arabic’s role as a central language for history, religion, science, and culture, with extensive use up to the 17th century.

In addition, Arabic is sometimes mistakenly seen as exclusively tied to Islam, but it has been a vital language for Christian communities as well. Although often associated with Islam, Arabic has long been used in Christian texts, liturgy, and daily life. Many Arab Christians speak Arabic as their native language, and it has been used in Christian liturgy, theological writings, and everyday communication for centuries

Thus, the New Chronology cannot explain the foundation inscription if it is associated with the Parthenon Mosque, as no Islamic or Arabic conquest occurred before the 15th century. According to New Chronology, despite the possible presence of Islamic elements, the Parthenon predates the Ottoman conquest and was originally established as a Christian church.

All viewpoints regarding Athens' history, whether from mainstream academia or alternative theories, agree that before the Ottoman conquest, the city did not have any significant Islamic or Arabic presence. This consensus is especially evident in the absence of evidence for a Grand Mosque or similar Islamic architectural structures within Athens during that period.

Drawing a definitive conclusion is still challenging because the available evidence is insufficient and scattered.

Conclusion

The Proto-Islam school suggests that early Islam initially encompassed a "Believers' Movement" that included pious individuals from different traditions like Judaism and Christianity, and only later evolving into a distinct religion. This view of a fluid early religious identity could potentially offer a framework for understanding the presence of Islamic elements or a "proto-Islamic" structure in a region like Athens at an earlier date than the formal establishment of Islam as a dominant force there.

The New Chronology, as proposed by Anatoly Fomenko and Postnikov suggests that the Parthenon might not be an ancient Greek temple but could instead be a medieval Christian structure, potentially constructed as late as the 13th century or even in the second half of the 14th century AD. From this perspective, its conversion into a mosque around 1460 may have been a gradual transition rather than an abrupt change, with religious elements coexisting before being formally separated into different traditions.

Between the 10th and 14th centuries, a structure integrating elements of Christianity, Islam, and remnants of pagan traditions was erected atop the Acropolis hills. Its minaret, incorporating intertwined Christian and Islamic architectural elements, may have borne a foundation inscription of a proto-mosque. The Arabic language of the time, along with Kufic script, belonged to the same shared Christian-Islamic cultural sphere. It was built for believers of an evolving religious tradition. A political, religious, or spiritual leader—referred to as “the commander of believers”—commissioned its construction, though his identity remains unknown to us.

Further Speculations and Open Questions

The proto-mosque theory can be further expanded to other interesting and challenging topics:

What happened on September 26, 1687? Why was the Acropolis fortified with walls and reinforced towers? Based on new findings I have proposed, the Acropolis functioned as a fortified castle. It served as a refuge for the "Believers." Until the mercenary army captured it in 1687, the Believers used the Acropolis as a sanctuary. They were massacred, and the mosque was destroyed during that event. In the 19th century, the castle and remaining structures were removed in the name of restoration. This perspective, viewing the Acropolis as a refuge and castle for believers, explains why there is almost no detailed information about the interior of the church or mosque. It also accounts for why all illustrations are from distant viewpoints. This perspective underscores its function as a defensive stronghold rather than as a monument intended for the attendance of non-believers.

Did the Parthenon have a roof? During the 1687 siege, how did the explosive projectile pass through a roof to ignite the stored gunpowder? Furthermore, the relationship between the minaret and the roof is questionable. Was the minaret projecting from the roof, or was it integrated into its structure? The noticeable absence of roofing debris after the explosion is suspicious. Such observations could suggest that the Parthenon Mosque might have been an open-air structure without a roof.

Based on conventional views, the prominence of Kufic script in Islamic art and inscriptions is associated with the Islamic Golden Age, spanning from the 8th to the 13th centuries. However, probably this period represents the golden age of “Believers,” which was present in later periods— in fact, from the 11th to the 16th centuries.

Referring back to my previous posts, the reader can guess why objects bearing Kufic script have disappeared from the area around the Tomb of Cyrus. In addition, remember that the site functioned as a roofless, open-air mosque, surrounded by columns. Furthermore, could the lament of Athens originally have referred to the massacre of believers inside the citadel of the Acropolis?

Reference:

Barletta, B. A. (2018). The first photograph of the Parthenon: An architectural study. University of Chicago Press.

Britannica. (1998). Parthenon history.

Crone, P., & Cook, M. (1977). Hagarism: The making of the Islamic world. Cambridge University Press.

Donner, F. M. (2010). Muhammad and the believers: At the origins of Islam. Harvard University Press.

Etlin, R. A. (2008). Modernism in the city: Architecture, interiors, and urban forms. University of Chicago Press.

Fomenko, A. (2003–2015). History: Fiction or science? (Vol. 4). Mitheograf.

Fowden, G. (2019). Before and after Muhammad: The first millennium refocused. Princeton University Press.

Haselberger, L. (2014). Marble inscriptions in Athens. Archaeological Review.

Hoyland, R. (2015). In God’s path: The Arab conquests and the creation of an Islamic empire. Oxford University Press.

Hurwit, J. M. (2012). The Parthenon and the Greek temple. Yale University Press.

Kallet, M. (2010). The Ottoman conversion of the Parthenon Mosque. History Acropolis.

Miles, G. (1958). The Arab mosque in Athens. American Numismatic Society.

Neils, J. (2005). The Parthenon: From antiquity to the present. Cambridge University Press.

Ousterhout, R. (2018). Byzantine architecture and its influence. Oxford University Press.

Palagia, O. (2013). The Parthenon and its sculptures. Cambridge University Press.

Setton, K. M. (1954). Athens under the Saracens? Speculum, 29(1), 50–70.

Szegedy-Maszak, A. (2013). The photographic history of the Acropolis. Princeton University Press.

Timetoast. (2025). Historical timeline of the Parthenon.

Travlos, J. (1971). The topography of ancient Athens. National Research Foundation.

Wikipedia. (2025). History of the Parthenon.

References

Barletta, B. A. (2018). The architecture and architects of the Classical Parthenon. Cambridge University Press.

Britannica. (1998, July 20). Kūfic script. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Kufic-script

Donner, F. M. (2010). Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Harvard University Press.

Etlin, R. A. (2008). The Parthenon in the modern era. Princeton University Press.

Fomenko, A. T., & Nosovsky, G. V. (2023). Предисловие к книге “Старые русские деньги”. Chronologia.

Fomenko, A. (2003-2015). History: Fiction or science? (22 books in 1) (p. 903). Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/history-fiction-or-science-2003-2015-22-books-in-1-fomenko-anatoly/page/n902/mode/1up

Fowden, E. K. (2019). The Parthenon Mosque, King Solomon and the Greek Sages. In M. Georgopoulou & K. Thanasakis (Eds.), Ottoman Athens: Archaeology, Topography, History (pp. 69-95). Athens

Finkel, C. (2005). Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire. Basic Books.

Gibb, H. A. R. (1979). The Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 4: Islamic Society and Institutions. Cambridge University Press.

Haselberger, L. (2014). Bending the truth: Curvature and other refinements of the Parthenon. Yale University Press.

Hoyland, R. (2015). In God's Path: The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire. Oxford University Press.

Hurwit, J. M. (2012). Space and theme: The setting of the Parthenon. Oxford University Press.

Kallet, L. (2010). Wealth, power, and prestige: Athens at home and abroad. Harvard University Press.

Lapatin, K. (2011). The statue of Athena and other treasures in the Parthenon. Getty Publications.

Neils, J. (Ed.). (2005). The Parthenon: From antiquity to the present. Cambridge University Press.

Ousterhout, R. (2018). "Bestride the very peak of heaven": The Parthenon after antiquity. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Palagia, O. (2013). Fire from heaven: Pediments and Akroteria of the Parthenon. Routledge.

Postnikov, M. M. (1997). A critical study of the chronology of the ancient world. East and Middle Ages. Volume 3.

Setton, K. M. (1954). On the Raids of the Moslems in the Aegean in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries and Their Alleged Occupation of Athens. American Journal of Archaeology, 58(4), 311–319. http://www.jstor.org/stable/500384

Timetoast. (2025, March 6). Islamic calligraphy timeline. https://www.timetoast.com/timelines/islamic-calligraphy

Wansbrough, J. (1977). Quranic Studies: Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation. Oxford University Press.

Wikipedia. (2025, May 2). Kufic. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kufic

статья получена 30.05.2025